Reflections on my Birthday...Remembering Dad

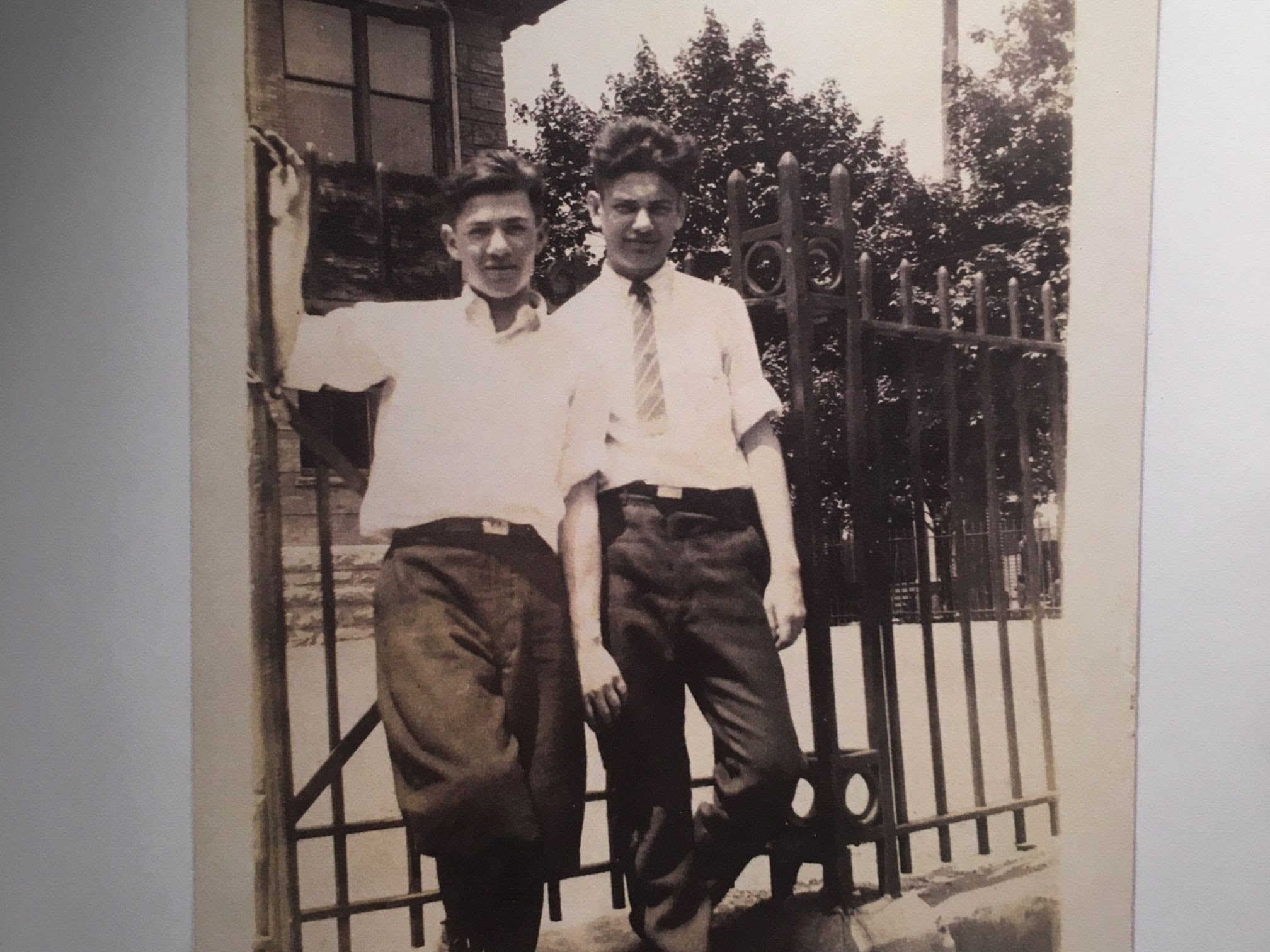

A 1924 photograph of my father and his best friend, Irving Bober, is attached. Dad was 16, Irving 17, and their friendship endured until dad’s death. I offer this memoir as a tribute to my father, a man I hold in highest esteem.

My father, attorney Benjamin Katz of Passaic, taught me more about love than any man I know. He did this by example, and I never got around to thanking him, because sadly, he died before those words were uttered.

Dad is long gone. He died too young at age sixty-seven - quickly and without prolonged agony. He was at his desk, when his final breath was drawn. It seems fitting that he would leave the world in this way. When I picture him, he is always at his desk, leaning over his "lawyerly" papers, or tending to some personal matter. He was busy. Involved. Attentive. Happy.

He tended to me, too, not as legal counsel, but as a father to a daughter, who needed guidance, and perhaps an available ear that was always receptive to whatever "crisis du jour" I was offering up. He was my best buddy - a parent with boundless benefits.

Ben Katz was fully engaged in whatever it was that brought me to his study. He was acutely sensitive, reading my moods, intuitively knowing when to advise, or when it was best to retreat. He listened without distraction or judgment.

There was a summer when, at seventeen, I was recovering from what the French refer to as ‘un coeur bris My heartthrob, Joey, a nice Passaic boy, was about to move away. Romance was in the air when Joey and I professed our undying devotion. I believe the word "eternity" was uttered in between a procession of innocent kisses that went along with our skewed notions of love.

Joey and I parted ways on a steamy August night when the air was thick with the aroma of honeysuckle, and fireflies flickered over my backyard lawn. We clung to each other with adolescent agony, until my father's sudden appearance at the back door jolted us back to reality. The sound of the screen door slamming shut, and my dad pointing to his watch, sent Joey running for cover as I disappeared into the house.

A month later, Joey wrote from California, informing me he had met Amanda to whom he was undoubtedly also professing his undying love, abandoning me to the heartbreak of believing I was doomed to face a life of loneliness and despair. The fallout of this rested with my father to whom I poured my heart out as I sat in his study, grabbing tissues and bemoaning my fate. He listened, his fingers folded together, as though there was nothing more pressing at that moment than this dramatic breakup and its tragic repercussions.

"I'll never get over it," I wailed through a barrage of tears. My dad leaned forward; his steely blue-gray eyes fixed on mine. "No," he said, "you won't get over it. But you will get past it."

Such were the pivotal moments my father and I shared. He was there for many of them and, sadly, missed a few. When I gave birth to my daughter, Elizabeth, he was the first one in the room, cracking open a bottle of champagne, heralding the arrival of his new granddaughter. As a grandfather he was exemplary; as a father, an indispensable role model.

For years, he and I dined together every Tuesday evening at a variety of different restaurants, never missing one of these ritualistic occasions. It was our time to discuss the week’s events, and solve any prevailing problems. This tradition lasted until his death, long after I had moved away. He died on a Tuesday, “our night” which seemed appropriately poignant.

March 21st, is my birthday. If my dad were here we would be celebrating its arrival in his inimitable style. He was there to honor many similar milestones throughout the many phases of my development, birthdays being just a few. Celebrations needed no justification. Small but significant moments were reason enough. That was part of his enduring charm: his eagerness to be a willing participant in my life. And I would occasionally write him notes:

Dear Dad,

Don’t forget tomorrow you promised to take me swimming at the lake. Love, J.

This was just another of a long steam of notes left on Saturday nights when my dad and mom were out for the evening. By the time they arrived home, it was waiting for him on the stair banister.

Early the next morning, we were up and running, with swin suits, and sandwiches in tow, made fresh at Berman's Deli. Berman's was on Broadway, across the street from the famous Hollander's fruit and produce market, jokingly referred to by its customers as Tiffany's because it was so expensive. That, along with thermoses filled with chilled lemonade, prepared by my mom,, who waved us goodbye as dad and I traveled off into our day. My mother, Eva Tobin Katz, often declined, preferring to stay at home and catch up on some quiet time. In that way, everyone's needs were satisfied.

Our favorite "swimming hole" was Lake Hopatcong. The drive seemed endless. The reality was it was just under 20-miles, and to me it was a sacred excursion - a destination filled with happy moments. The swimming itself was just a small part of this scenario. It was the time spent with my father that was the sweetest of all,, and such moments spanned years.

Another note: Dear Dad, If you can’t take me bike riding tomorrow because you’re busy with your briefs, I’ll understand. Love, J.

But he always made time for me, as we biked over to Third Ward Park, where, in winter, we ice skated on the pond ending up huddled on a bench, this time enjoying thermoses of hot chocolate.

Dear Dad, There’s a great movie at the Montauk Theater. Let’s go. Love, J.

And we did. It was an Esther Williams flick, where Esther dove flawlessly into a pool of water while a bevy of bathing beauties fluttered around her, encasing her in large colorful feathers, which never got wet. These movie jaunts also included sharing a bag of popcorn, and enough candy bars to render us both sickeningly gratified. Afterwards, we trekked over to Feitlins for hot dogs.

It is hard to adequately explain now, decades later, the thrill of those hours spent with my father. In retrospect, they remain perfect little remnants of my past - bejeweled moments that twinkle brightly and remain even in absentia, bittersweetly intact.

My father died on a frigid February 15th. We never had the chance to say goodbye. I had always expected his closing act would be grand and resonant. That I would be by his side bidding my final adieu, as he professed profound words of wisdom for me to carry away. I envisioned a huge sendoff. Fanfare. Streamers. But his death was quiet and uncelebrated. He died alone in his study where we had spent endless hours dissecting my life - an astonishing yet predictable coincidence.

Looking back now on the rim of a new birthday year, I recall it all, and the impact we had on each other's lives. There were times I disappointed him, made him furious, made him laugh, made him proud. Birthdays were stepping-stones toward an ever-evolving, unpredictable future, and we accumulated many of them together.

After his death, I wondered if I would ever recover. But he was too large in scope, too charismatic, wise, funny and enormous a presence for that to ever happen.

Each birthday, the memories surface, and my father's image resonates still. The loss is palpable.

"You won't get over it," he had reminded me so long ago, "but you will get past it,"

I've been working on that for years. I'm not quite there.

Judith Marks-White

Ben Katz

Ben Katz & Irving Bober

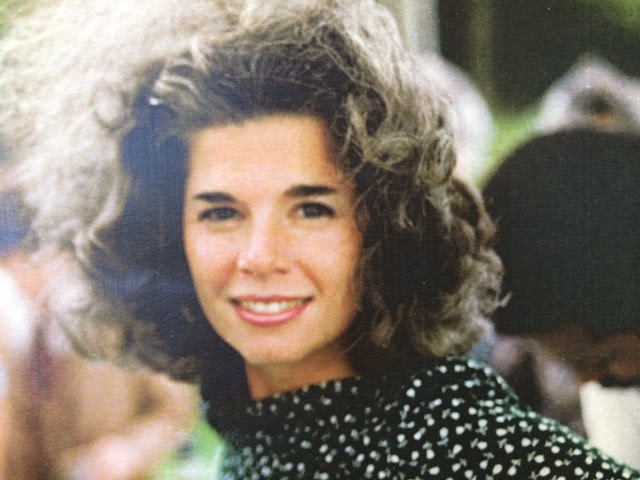

Judith Marks-White

Summer at Lake Hopatcong