Summer Nights with Dad: Memories of Market Street… and Beyond

It's summer. A heat wave enveloped us in a lethargic trance. My dad and I were visiting his parents - my grandma Hannah and Grandpa Sam - on Passaic’s Columbia Avenue, where women sat on front porches fanning themselves with handkerchiefs, and men in short-sleeved shirts exited their cars, removing ties and exchanging pleasantries with friends.

On other such afternoons, when I was much younger, we visited my mother’s mother, Anna, who lived in a large Victorian house on President Street, where blue hydrangeas flanked the grand winding porch, and the smell of lilacs was always in the air. Sadly, Anna Tobin died when I was four, my grandpa James before her, leaving me a collection of grandma’s gold rings, and enough memoirs to last a lifetime.

I was on the brink of adolescence when everything seemed overheated and sultry. Inside my paternal grandmother's house, the scent of perfume, Witch Hazel and Ajax made me heady, Grandma Hannah wiped her face with a damp dishtowel, and removed a tray of cookies from the oven. She was oblivious to the fact that the kitchen temperature felt like a hundred degrees.

For me, all of this was a magical time when life stood still and people moved slowly. Even the birds took a breather, settling themselves on telephone wires, too tired to spread their wings and fly.On other evenings, I sat on my front lawn waiting for my father’s car to turn the corner into our street, signaling his arrival home from the office. After dinner, we would go downtown to Market Street for Sal’s Italian ices.

Downtown Passaic was different from the upper Main Avenue I knew, with its fancy shops, movie theaters - (Montauk, Central, Lincoln and Capitol) - and restaurants like The Ritz with the flat-footed waiter, Feitlin’s deli, and later, The Garden, and the iconic Howe Cafeteria where my father met his cronies before going off to the office.

Sunday nights meant dinner at Gene Boyle’s, where an organ played in the grill room, and Gene personally greeted all his patrons. We had a stranding Sunday dinner reservation, and I always ordered the veal parmigiana, which has yet to be replicated. And there was Wechsler’s Department Store where the handsome Joel Wechsler welcomed us in, and where I bought my first Pixie Pink Charles of the Ritz lipstick.

And then there was Market Street, which by comparison was fraught with intrigue, and by my parents’ standards, was dangerous, foreboding, and, for me, all the more exciting.

On these early summer evenings, leaving my protected little world and holding tightly to my father’s hand, we ventured forth to Capuana’s Pool Hall. There, toothless men with tattoos punctuating their withered arms sat outside on orange crates, checking out the women as they sauntered by in their summer dresses. When a pretty girl appeared, the men raised their beer bottles in salute, providing wolf whistles to seal the deal.

Our trips to Market Street were not only to get a glimpse of life on the edge, but to visit Sal Capuana, the “Ice Man” who owned the garage next door to his brother and to see Lonnie Capuana’s Funeral Parlor, where an array of caskets adorned the glass front window.

In the back of Sal’s garage was an auto body shop where dad had his car serviced. In the front stood large solid blocks of ice hissing their frozen steam into the air. Next to that sat a large tub filled with chopped ice, to which Sal added pounds of lemon and sugar, creating his legendary "shalali." It was where on hot summer evenings before I left for camp, dad and I made nightly journeys to quell our cravings. Part of the thrill was watching Sal scoop chunks of lemon ice into the white-pleated paper cups. While dad stood around shooting the breeze with Sal, I sat on a wooden barrel, reading Archie comics, and swallowing down the remaining sugary liquid, so sweet it made my teeth squeak.

One evening in early June, on one of our nightly excursions, Sal’s son, Mickey, home from the army for several months, was rotating tires in the back of the garage. I was fifteen, and Mickey, the ‘older man’ was my adolescent heartthrob. His dark, greasy hair framed his face, and dressed in a white T-shirt and blue jeans, his pompadour rising like a black wave, he looked like an Italian movie star. While Sal regaled dad with stories, I stared at Mickey, hardly able to catch my breath. When it was time to go, Mickey, pausing for a mere moment to notice me, winked, and rolled himself underneath a large Cadillac, fading out of sight.

I remember my knees buckling; my cheeks glowing, as I stood there, my fingers sticky from lemon ices, watching Mickey disappear from view with only his denim-covered legs protruding from beneath the car. From then on it wasn’t only lemon ices that lured me to Sal’s. I had a new mission: to catch another glimpse of Mickey Capuana.

Late August, when I was back from the secluded Adirondacks, it was time to get ready for school. Mickey had returned to the army, and somehow Sal’s ices didn’t hold the same allure once the crispness of September rolled around. But each year as summer approached, I recalled Sal’s garage, and my awakening to matters of the heart.

All these years later, I still find myself thinking about Passaic. Grown now, and living in Connecticut, the memories linger, and remain vivid mental snapshots: I recall trips with dad to Forstsmann woolen mill, where I stood at the pasture gate feeding Wonder bread to the sheep. Those first spring evenings when I jumped rope with my neighborhood friends, and playing hide-and-go-seek in the large empty lot next to my house, concealing our bodies beneath a pile of out-of-control weeds.

I remember the cheeseburgers at Wasser’s, the patent leather shoes at Simbals, Gero jewelers, Jack Eisner’s toy store, and the orange and black buses that carried us into New York when my father didn’t want to drive.

I recently wrote a poem in tribute to Passaic which best exemplifies and commemorates those early days I hold most dear:

Passaic, New Jersey

I’m twelve and barefoot,

That time of day

When the best parts of summer happen.

Caught between a stretch of

Afternoon and sunset,

Mothers shout from behind screen doors,

Fathers, home from work

Punctuate the street

With Buicks, Oldsmobiles and Chevys.

The smell of suppers waft through

Open windows.

Pots of red geraniums, bow in procession, beckoning us home.

Ritchie from across the street with his

Green Hornet comics -

Patty with her chipped tooth and jump rope,

Mr. Smoke with his cigar, and his dog named Alger Hiss,

Decorate the neighborhood.

I bounce my pink Spaldeen as far as my front porch

To smiles, wide as watermelon –

Hugs, round as melons –

My mother’s lips, red as dark cherries.

Many summers later in some far-off distant future

I still recall those afternoons on Idaho Street

When my bedroom smelled of lilacs,

Put there by Maddie,

Who made the best fried chicken,

Scraped the day’s dirt off my overalls,

Kept my secrets

Hidden deep inside

Her apron pockets.

But in the end, my thoughts always return to Sal's, to Mickey and the shalali. Instead, I buy myself a pint of lemon sorbet, trying to replicate the old memories, but it’s never quite the same. What does remain, however, are those sweltering summer nights, Mickey prostrated under the car, and my dad pretending not to notice his daughter’s budding flight into womanhood, while he and Sal caught up with the latest news of the moment.

I have never forgotten those evenings on Market Street where life was steamy, tough and intoxicating, as I stood young and restless on the rim of adulthood. Those were the summers when I believed that nothing bad could happen to me as long as I kept my hand gripped tightly in my dad’s, as we walked along into my yet unknown future waiting to be explored.

Judith Marks-White, Friend of the JHSNJ

Judith is a Westport News (CT) humor/essay columnist, and author of Seducing Harry and Bachelor Degree (Random House). She free-lances for newspapers and magazines throughout the country, and she lectures widely. She taught college English/writing for many years, and now conducts writing workshops throughout Connecticut. She is presently working on another book.

Judith (nee Katz) grew up in Passaic, and attended the Passaic Collegiate School. Her father was attorney, Benjamin D. Katz and mother, Eva Tobin Katz of Passaic. Judith lives in Westport, Connecticut

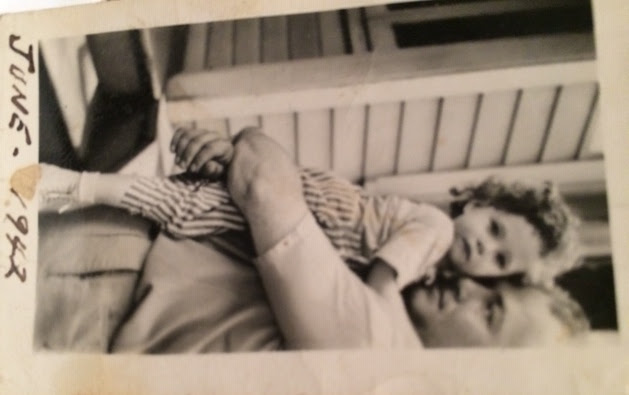

Dad, Benjamin Katz with Judith Marks-White (née Judith Katz)

Attorney Benjamin D. Katz, father of Judith Mark-White (Nee Judith Katz)